This is a continuation of the very lengthy discussion in the comments section of my blog entry An Open Letter to My Friends in the Emerging Church. If you want to follow that interesting discussion, start there first and then continue on here.

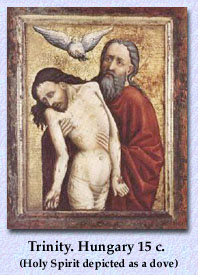

This is a continuation of the very lengthy discussion in the comments section of my blog entry An Open Letter to My Friends in the Emerging Church. If you want to follow that interesting discussion, start there first and then continue on here.The Trinity is not just (as Chris puts it in the earlier comments section) "a very useful concept to understand what God's trying to tell us." The Trinity is God. Of course the doctrine of the Trinity is a construct of language and of the mind, but so is all speech and all thought. Anything we say about God is metaphorical, not just what we say about the Trinity. Nobody claims, least of all the Trintarian theologians of the Nicene era, that the human mind can fully comprehend the being of God. All is mystery to us except what has been revealed. In Luther's language the only God we see is the God who is clothed in Jesus Christ. But what the appearance of Jesus Christ drives us to inevitably is a God who is Triune. What the church confesses about the Triune nature of God is not something spun out of the air by rampant Hellenism. It was religion before it was theology. All formal theology has as its precedent the actual experience of God in the Christian community and in the world. It's not something begun in the rarified atmosphere of abstract thought (though it sometimes may end up there). That Trinitarian language (like all language about God) is limited is simply a given in all theological discourse. As Augustine put it, "When the question is asked, What three? human language labours altogether under great poverty of speech. The answer, however, is given, three ‘persons,’ not that it might be (completely) spoken, but that it might not be left (wholly) unspoken.” So it is a straw man argument to say that the Trinity is something not very important because no one can completely wrap his or head around it. To follow this line of reasoning would be to confess nothing about God at all, since we cannot do so comprehensively.

Chris says that my "fascination with [theology] is more academic than practical. Does knowing the trinity exists make you do your mission work better?" My response to the first part of the sentence is, brother, you couldn't be more wrong about that. My answer to the question about the Trinity and mission is a resounding "Yes." On the first point - Theology is a discrete academic discipline in many universities and other institutes of higher learning, yes. And though I teach theology in one such place, and am involved in the academic discourse of the discipline, my primary commitment to theology is as a Christian for whom it matters to think seriously about God. Theology is the business of every Christian, not just academics and professional theologians. Michael Jinkins helpfully reminds us that theology is reflection upon all of life, not just upon “religious” matters, when he says "Theology is the essential business of faithful reflection on human life lived consciously in the presence of God." (Invitation to Theology, 17.) Nothing could be more practical than this.

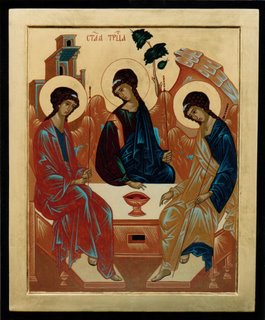

Now to the question, "Does knowing the trinity exists make you do your mission work better?" Absolutely it does yes. The most significant (re)discovery of twentieth century theologians was that God's existence as a "Being-in-Communion" (and not simply a divine Monad) is the fundamental beginning point of all Christian thought and action. This rediscovery of the Trinity as the beginning point of all theology and practice, beginning with Karl Barth, was the single most influential insight in the development of theology in a post-modern (please note the hyphen) world. Chris, as one who hopes one day to be a professor of theology, familiarity with this direction in theology should be of crucial importance to you. No-one hated philosophical theology more than Barth (with the possible exception of Luther), but he didn't find the Trinity in the philosophers. He found the Triune God in the Bible and inescapably in the Person of Jesus Christ. It is because God is in Godself a Being-in-relation, and we are made in the image of the Triune God, that we are called to reflect that same image in all of our interaction with others. We are called to be open to God and to others in outgoing, self-forgetting, love. The trinitarian relations within the Godhead whereby the Father gives his Son for the life of the world, the Son gives glory to his Father through unstinting, though costly obedience, and the Holy Spirit is given to glorify, not himself, but both the Father and the Son, provide the model for our relationships to others. Believers, in their relationships with one another, and with the world, are caught up into the “ecstatic” fellowship of the Divine Family. The believer is called to be one who shares with the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in an “others-focused” orientation. Surely this is the only proper foundation for mission.

Modern Trinitarian theology has helped us to see that the doctrine of the Trinity begins with a focus, not on God’s ontological being, but on God’s saving activity. It centres on Christ’s birth, life, death, resurrection, ascension, and the gift of the Holy Spirit. The doctrine of the Trinity, rather than being a doctrine derived from philosophical reflection on the nature of Absolute Being (a reflection which always tilts toward sheer monotheism or monarchianism), is rather the result of rational reflection on the saving activity of God in Christ. These divine occurrences confront human reason with the realization that only a triune God can account for them.

Modern Trinitarian theology has helped us to see that the doctrine of the Trinity begins with a focus, not on God’s ontological being, but on God’s saving activity. It centres on Christ’s birth, life, death, resurrection, ascension, and the gift of the Holy Spirit. The doctrine of the Trinity, rather than being a doctrine derived from philosophical reflection on the nature of Absolute Being (a reflection which always tilts toward sheer monotheism or monarchianism), is rather the result of rational reflection on the saving activity of God in Christ. These divine occurrences confront human reason with the realization that only a triune God can account for them.Eric Macall wrote in Whatever Happened to the Human Mind (1980) : "The Trinity is not primarily a doctrine, any more than the Incarnation is primarily a doctrine. There is a doctrine about the Trinity, as there are doctrines about many other facts of existence, but if Christianity is true, the Trinity is not a doctrine, the Trinity is God. And the fact that God is Trinity - that in a profound and mysterious way, there are three divine Persons eternally united in one life of complete perfection and beatitude - is not a piece of gratuitous mystification, thrust by dictatorial clergymen, down the throats of an unwilling but helpless laity, and therefore to be accepted, if at all, with reluctance and discontent. It is the secret of God’s most intimate life and being, into which, in his infinite love and generosity, he has admitted us; and it is therefore to be accepted with amazed and exulted gratitude."

In the so-called postmodern world, it is more or less a given that individuals are not lone atoms but persons in relation. There is no longer any "autonomous man" (now a thankfully debunked modernist myth). Each person is who that person is because of intimate connections with other persons. The doctrine of the Trinity speaks profoundly to this realization, for it tells us that God’s own being is constituted in precisely this way - God is a being in communion. This communion is, moreover, a loving communion. As Robert Wilkin has it, “The doctrine of the Trinity reaches to the deepest recesses of the soul and helps us know the majesty of God’s presence and the mystery of his love. Love is the most authentic mark of the Christian life, and love among humans, as within God, requires community with others and a sharing of the deepest kind.”

After all, to which God are we introducing people when we engage in mission? Not Plato's Unmoved Mover, or the Absolute Monad of Arianism or of Universalism, but the God whose Name is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This is not some vague Higher Power or Supreme Being, but a Particular God - a God with a history. This is the God whose Name we all received at our Baptism, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (yes, and of Athanasius too), who brought our ancestors through the Red Sea, who transformed the world through the cross and the empty tomb. Chris says we can learn a lot from Buddhists and Mormons, and of course we need to be respectful listeners to all people. We cannot say we disagree until we can first say we understand and the church has not always been good at this. But what will happen if we lose the distinctiveness of the God we confess, what if we forget God's Name, what if we forget our Story, what will we have to offer in the dialogue? If emergent/missional churches are going to sit loose on the Trinity I truly fear for them.

Finally (if you've got this far you're probably one of the few), Chris thinks I'm mistaken when I say my church is "traditional" and that in fact we are "missional" but don't know it. I think we are using the word "traditional" in completely different senses (which is a very bad basis for dialogue). Chris, you seem to use it to mean something like this (correct me if I'm wrong) - "evangelical churches who are unfaithful to the Gospel because they are so consumed by running their own programmes that they are not engaged in mission beyond their own four walls." You see, to me there is nothing traditional about that at all. Some churches (of all kinds) are stuck in this pattern and some churches are not. I would suggest that far fewer are as dead in this respect as the emergent/missional churches claim. How then might I define my church as "traditional" and thus different from a typical emergent approach?

We believe that God calls us to gather together on the first day of each week in commemoration of the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. It's not a sabbath - it's the Lord's Day - a mini-Easter every Sunday (or if you like every Easter is a Big Sunday). Emergent/missional churches don't think it's all that important on which day they meet or indeed if they meet weekly at all. Any day or time of the week will do; it's all the same to the Lord.

When we gather we enact a liturgy that narrates the story of what God has done in Christ. We enjoy preaching and we like it to be from the pulpit, a symbol, not of the minister's authority, but of the authority of Holy Scripture. We take up an offering each week because we think Christians should discipline their love of money and because we want to support and enable the church, including the pastor, in its ministry. We don't think it's absolutely necessary to sing hymns or any other kind of songs, but we embrace music (especially hymnody) gratefully and enthusiastically. Emergent/missional churches don't typically think too much of these patterns of worship, though some will do them. But worship is just as valid if it's meeting with a Christian friend down at the local cafe and having a talk about Jesus. We love to meet our friends at the cafe too but we wouldn't feel, like we had worshipped or "been to church." That's one of the things that makes us "traditional."

Like emergent/missional churches we wholeheartedly believe that ministry belongs to the whole people of God and that the church should do its utmost to equip and enable all of its members to fulfil their task in ministry. However, we still believe God calls men and women to a Ministry of Word, Sacrament, and Order - to have a shepherding responsibility over a Christian congregation. It would certainly be wrong for our pastors to big note themselves or lord it over their flocks, but we want to honour them and respect them as the Scriptures command us. We believe that a ministry of preaching, teaching, and pastoral care requires a high level of professional skill and knowledge development, so we want our ministerial candidates to have a degree in theology as well as whatever other specialised training helps them in their ministry. Just as we want the members of our congregation who are doctors, plumbers, or garbage collectors to give themsleves wholeheartedly to their life's vocation, to be recompensed fairly for their labours and to have safe and just workplace conditions, so we want our pastors to have the same. In keeping with this, a large proportion of our budget goes to pastoral support and we are unapologetic about this. This makes us "traditional." Emergent/missional churches tend to frown on professional clergy as a waste of money and resources and feel (again correct me if I'm wrong) that the system obscures the priesthood and ministry of all believers, so that the pastor does all the work and nobody else does anything. It's okay to operate without paid pastors of course, but it cannot be the only way. We (and millions like us) are happy with the traditional model of pastoral supply and apparently still reasonably "missional" as well.

To me "traditional" just means doing things pretty much the way the church has always done it, and "emergent" means trying something different. By that definition our congregation is "traditional" and emergent churches are not. One can be just as effective in mission as another.

Most of my life I have attended 'traditional' churches. In fact, as a child I attended, for a number of years, a church that Glen pastored.

ReplyDeleteNow as an adult and with a child of my own I am attending a traditional presbyterian church.

To me, there is something really wonderful about attending church on Sundays with brothers and sisters in Christ to worship the Lord. For me (a total non-academic but a busy mother of a young child) it provides the strength and encouragement I need to get through the coming week.

Some weeks the only slightly 'missional' thing that I do is teaching my 3 year old to say her [traditional] prayers at bedtime.

All churches are not made up of people who feel called to or want to find alternatives to the way things are done and have always been done. Traditional churches can be spiritual havens and places of worship for everyday people of all walks of life committed to serving the Lord in a way that they feel honors Him.

Thank you Donna for the beautiful simplicity of your reply.

ReplyDeleteYou're right in saying that I favor a definition of "traditional" as a stuck-in-the-ruts evangelical thing. And it's a fantastic point: having different definitions on these things makes for a bad dialogue.

ReplyDeleteWhich is why I asked you, in my first reply (many words ago) for a firm definition (as you see it) of "Emergent" ... frankly I don't think we see eye-to-eye on that either.

As Mark Driscoll puts it, there are four broad categories that fit within "emerging christianity": "Emergent" christians, who tend to play with theology and dismiss most church history in favor of their own interpretations. I've even heard of them removing books from their bibles because they didn't think they 'fit'. They are to be ignored, as they are both the minority AND heretical in so many ways. They often remove themselves from discussion with the rest of the church, instead, isolating themselves and then firing off diatribes at the rest of us and ignoring our responses.

They are more cultish than Christian. But don't worry about them. But also I'd recommend you avoid using the word "emergent," because it denotes something very bad to those of us in the emerging church.

There are churches who fancy putting a new coat of paint over traditional (read: "what we're used to") practices of worship services, but essentially acknowledging the usual theology of their denomination. Instead of services in a church with a worsihp team or choir up front, they may substitute a simple cross up front and use "stations" during worship, move the band to the back (for humility), and all sorts of other things. But they're not really changing much, as they tend to still be "attractional" (evangelism happens by bringing non-Christians INTO the church, attracting them by their service) in their methods, rather than "incarnational" (mission happens in the non-Christian's native community).

The third is the "house church",

The other end of the spectrum is "missional" church, a category that Driscoll seems the most interested in. Here, the only binding characteristic is that mission is done in the host community, rather than inside a church building removed from "the world." It has an infinite possible variations on service style, usage, the "communal" part of being Christian, but all missional churches are more intersted in going OUT to the host community rather than bringing the host community TO THEM.

Now. Tell me you're not Missional. The categories can sometimes be mixed, and "missional-house-church" is how I'd classify my particular church, though we call ourselves a "network" church because of the subculture of small-groups we try to emphasize (but we're not "emergent"). To watch the video, click here.

On another note: please don't think I'm trying to downplay the trinity. My point is merely that when it comes down to it, I'd prefer we focus on mission than trying to understand the trinity. I'm not saying we can't do both (and we SHOULD do both, as that is truly seeking God), and once again, I AGREE - The scriptures RESONATE with trinitarian theology. But please, do not tell me that they are anything more than a construct that reflects the truth of God. To do so attmepts to limit God's vastness into a box you can understand, when in fact, we NEED to feel in awe. To understand God would be to control God, and he's made sure that we can't control him.

Your illustrations of emerging churches were interesting. I think that the only thing ANY of the emerging expressions have in common is their attention to mission. Other than that, their forms and expressions are all sort of free-for-all. Whether or not a pastor is paid or not, whether we use a service on sundays (which, if you want to get technical, the sabbath is Saturday, it was changed to Sunday back in the fourth century in a fit of anti-semitism, so you're already not observing the "traditional" sabbath), the style of music, etc. ... all of these things vary from church to church. There is no prescribed method in scripture. Frankly, there is no prescribed method in history either. The Celtic Church was different from the Roman Catholics, who in turn were different from the Eastern Orthodox, who in turn were different from the Lutherans, ... see how it adds up? You can't say that there IS a norm, because there never WAS one. The missional and emerging churches do not frown upon one form or another (well, not true, some do, but they're wrong to do so), but merely point out that the form should WORK for its host community. If your host community are people who prefer organ music and a sermon, great! If not, maybe that's not the best way to be missional in your community.

The other thing is how you defined worship. I just wrote a paper on this, and I'm curious why it is you think that worship is an event. Worship is not and never has been purely an event. COMMUNAL worsihp usually is, and I applaud that (and will be participating in it this sunday). However, WORSHIP, scripturally, is an ever-present reality; you worship continuously in your actions and thoughts, or at least, you're supposed to (yeah, sin gets in the way a lot).

I applaud your devotion to the regular liturgy, as it creates a rhythm in the lives of your congregants. We do it too! Just because we hold worship SERVICES only once every four weeks does not mean that we don't meet weekly for communal worship! We meet for learning and other forms of worship on other weeks. We meet one week in a different congregant's mission field, to pray for them and learn about the mission God has placed on their hearts. Another week we meet at a pub for fellowship and celebration. Another week we meet as our smaller cell groups in our individual suburbs to pray and work on mission there.

Not to mention the fact that sunday is not the biblically-prescribed sabbath; a sabbath is a day of rest, and as it happens regularly, it can happen regularly on other days. What day do pastors take as a sabbath? Certainly not sunday, because running a traditional church service is certainly not restful these days, and not saturdays, because those are usually spent preparing FOR church services. Most take Mondays off, to rest, be with their families, and recharge their batteries. If you believe that God has called YOUR community to meet on sundays, then fantastic - you should meet on sundays as a community. But don't try to impose that guideline on others when it's not biblically mandated. Encourage them to take A sabbath (as is scriptural), but don't force them to take YOUR sabbath.

Got some books for ya. "Organic Church," by Neil Cole, "Velvet Elvis" by Rob Bell, and "The Shaping of Things to Come" by Alan Hirsch and Michael Frost. Good stuff, the lot of them, and I'd encourage you to prayerfully consider the stuff they have to say.

Alicia - good on ya girl, way to smack us around. Unity is a good thing. Hopefully Glen and I are both still trying to discuss and learn from each other instead of getting mad at each other's stubbornness (right mate?) :)

Thanks for your good comments Alicia. Christian unity doesn't necessarily mean that we all have to agree or that we should never express disagreement. If anything on the previous posts was "other than loving" I apologise. We are called to love but also to "speak the truth in love" and sometimes it his hard to strike that balance. I am more than happy to live and let live on this point (the Lord knows we all have plenty of important work to be getting on with), but I wanted to open this discussion as a way of doing what you suggested (identify, lovingly correct, gather together to sort stuff out) only in the blogosphere. I certainly would want the discussion to be carried out graciously.

ReplyDeleteI'm not mad Chris nor (I hope) stubborn. Sorry if I misled anyone, but I don't believe Sunday is a sabbath or that Christians have any sabbath to observe at all. The sabbath was the sign of the covenant between God and Israel. It doesn't have transferability to Christians at all except for messianic Jews who observe it as part of their Jewish culture, and Adventists and Seventh-Day Baptists whose consciences lead them to worship on this day. We have a new covenant in Christ's blood. If there is a sign of that covenant it is the Eucharist. The earliest Christians were Jews and observed the Saturday sabbath as well as gathering early on the first day of the week to celebrate the resurrection. As the church became increasingly gentilised the sabbath observance dropped off.

ReplyDeleteThe idea that Sunday became the sabbath in the fourth century "in a fit of anti-semitism" is just historically wrong. To our shame there was plenty of anti-semitism in the patristic period, but Christians had gathered on Sunday for worship since the New Testament period. Second and third century writers reflect this well established practice long before the Constantinian era (poor old Constantine gets blamed for a lot of things - not that he was a saint or anything!) Observing Sunday as a Sabbath-like "day of rest" was not the early church practice and is really the invention of Scots Presbyterians in the seventeenth century. Methodists and other evangelicals followed suit but exegetically there is virtually no basis for such observance in the New Testament.

So to make myself clear, I do not believe that Sunday is a sabbath, and I would never seek to enforce it on anyone. I gave reasons in my earlier post why our congregation and 99.9% of all Christians over two millennia have worshipped on the first day of each week in celebration of Christ's resurrection. I follow the NT and Pauline principle that each one should observe whichever day his or her conscience dictates.