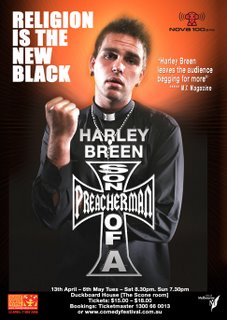

Son of a Preacher Man

The Boy Wonder and I went along to see Harley Breen's one man show Son of a Preacher Man in Flinders Lane last Tuesday night. It was crude, rude, irreverent...and very funny. It would be easy for a Christian to be offended at the material but it would be all too easy to rush and in and smugly condemn without asking what truth is being offered here. We need to hear his perspective on why the church doesn't appeal to so many like him who have left the church disillusioned figuring it has nothing to offer. For those who think this show may be just a cathartic exercise in axe-grinding against repressive parenting - think again. It's clear that Harley loves, respects, and admires his parents and that he respects the choices in life they have made, even though he hasn't chosen to make those choices himself. More often than not it is the people in the congregations that his parents served that get the most stick, and if you're a preacher's kid too I'm sure you'll have a bunch of similar stories to tell about the strange people who inhabit the pews of every suburban church.

The Boy Wonder and I went along to see Harley Breen's one man show Son of a Preacher Man in Flinders Lane last Tuesday night. It was crude, rude, irreverent...and very funny. It would be easy for a Christian to be offended at the material but it would be all too easy to rush and in and smugly condemn without asking what truth is being offered here. We need to hear his perspective on why the church doesn't appeal to so many like him who have left the church disillusioned figuring it has nothing to offer. For those who think this show may be just a cathartic exercise in axe-grinding against repressive parenting - think again. It's clear that Harley loves, respects, and admires his parents and that he respects the choices in life they have made, even though he hasn't chosen to make those choices himself. More often than not it is the people in the congregations that his parents served that get the most stick, and if you're a preacher's kid too I'm sure you'll have a bunch of similar stories to tell about the strange people who inhabit the pews of every suburban church.

Harley is at his best when he is sharing funny stories from his childhood - sibling rivalry, puberty, and adolesence all yield their hilarious moments. The slapstick disguised as political comment against the Howard government in the Gummy Bears routine is great. The show is weakest in its middle section when Harley dons the clerical garb and plays the part of a preacher on the take. The effeminate preacher intent only on exploiting people is a wornout cliche. I have no objection to lampooning the clergy as such (we're all fair game) but a more original approach was needed to lift this part of the show beyond the humdrum thing we're used to seeing on TV. It's the real Harley Breen that works best, not the two-dimensional caricature of this all-too easy to deride target.

In the medieval world, the jester was ostensibly for the purposes of entertaining the king and his court. But he also played a subversive role. With skill and craft he could use his humour to point out the vanity or folly of the kings' character or actions, thus turning a mirror on the royal personage. As an innocent child was needed to point out the fact that the emperor had no clothes in Hans Christian Anderson's folk tale, so it was the court fool who often played the role of pointing out the pretensions of royalty. Harley Breen's show turns a mirror on certain attitudes found in the church that are positively unChristian and need to be unmasked and repented of - the idea that Christians are by definition better people than all others (clearly not so), that Christians often show little respect for indigenous cultures and seek only to supplant them and replace them with European "civilization" (often, though by no means always, the case with missionaries), and that Christians can at times be violent toward those of other faiths.

One of Harley's Dad's former parishioners told him that his show was evil and blasphemous and that he was going straight to hell, apparently without seeing the irony that this was a rather "hellish" thing to say to another human being. But there is a difference between blasphemy and criticism. I once rebuked a youth camper for telling a distasteful joke about God and told him that we should be carefuil not to use the Lord's name in vain. Later in the camp he overheard me telling a joke about the church and he decided to rebuke me in turn. I told him there is a difference between mocking God and laughing at the church. It's a healthy thing to be able to laugh at oneself. Harley's show doesn't mock God so much as point out the inconsistencies of professing Christians, which is a different thing altogether.

There's a lot of truth in humour - we have to take it seriously (pun intended). The Danish philosopher and theologian Soren Kierkegaard saw the closest proximity between theology and comedy. Comedy sees tragedy from the viewpoint of its resolution, so comedy helps us transcend tragedy by placing it in proper perspective. This is why, for Kierkegaard, humour was the state of consciousness nearest to religion. Some like Harley Breen use humour to resolve the tragedy of the church's behaviour by walking away from it. Others, without denying the tragedy, choose to remain committed to the church, convinced that in its sinfulness it is really only a microcosm of all humanity, but convinced also that in the church (though not exclusively there) God offers his grace to those who need it. I'm reminded of the Docetists of the early church who were willing to accept that Christ was divine but could not accept that he was also human. It is the very humanness of the church, its fallenness, that many people find unacceptable. But the church does not claim to be a perfect society of saints (though admittedly some Christian movements have tried to make that claim.) It is always a "mixed multitide" of people on various stages of the way of Christ. And the Church exists also for those who cannot bring themselves to enter it or who walk away from it. It exists this way not because it is the only place where God is at work, but because Christ has united himself to his followers by calling them his friends, and, corporately, his Bride. It's okay to have a problem with the way the church behaves but if we have a problem with the Bride we do have to take it up with the Bridegroom.

In his final gag Harley tells of how he decided to try being a Buddhist for a day. He knew that according to the tenets of Buddhism he was supposed to respect all sentient beings, including the smallest creatures, so when he stepped on a bug, he grew angry with himself and kicked the dog. Now he felt even worse. Finally he saw a Buddhist monk, and he angrily and violently knocked him to the ground. Then came the punch line - "Well, I guess I'm still a Christian after all." If only the tragedy could be resolved so neatly. If violence or greed or bigotry or selfishness were uniquely Christian traits, we could solve the world's problems by getting rid of (or at least quarantining) all the Christians. But these things are human, not uniquely Christian, traits. The church tries to bear witness to a better way - to the way of Christ. That it does so inconsistently only shows that it is fully human. In the end, God is speaking both through and to the Son of a Preacher Man - for those who have ears to hear.

1 comment:

Great thoughts! I agree that we can take ourselves too seriously as the church. I love a bit of comedy myself, and like to think that I can laugh at things in myself and my church. But where do you draw the line? I guess there is a fine line that many people disagree over. Do we let people point out things that we are unaware of or uncomfortable with? Or do we react defensively and in doing so reinforce their sterotype (justifyable at times) of us? Hmmm...

Post a Comment