Ned Kelly and the Anglican Bishop

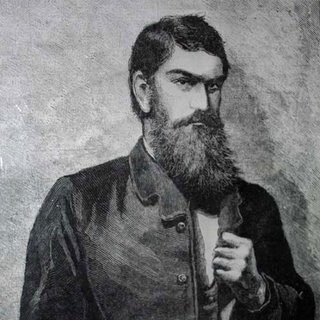

Bushrangers have been seen as heroes and champions of the underdog, who, Robin Hood style, robbed from the rich to give to the poor (or at least to unseat the rich from the arrogance of privilege). On the other hand, they have also been seen as mad dogs, murderers, scoundrels, and rebels, deserving the full weight of civilization’s unbending justice. Australia’s most famous bushranger Ned Kelly (1855-1880) has generated both sets of sympathies.

Bushrangers have been seen as heroes and champions of the underdog, who, Robin Hood style, robbed from the rich to give to the poor (or at least to unseat the rich from the arrogance of privilege). On the other hand, they have also been seen as mad dogs, murderers, scoundrels, and rebels, deserving the full weight of civilization’s unbending justice. Australia’s most famous bushranger Ned Kelly (1855-1880) has generated both sets of sympathies.

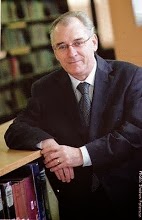

According to Bill Gammage, “Bushranger is an Australian word. It evokes bushcraft, daring, defiance, and freedom from convention, rather than crime or evil. It touches an Australian nerve [as evidenced by] G. T. Dicks’ 1992 A Bushranger Bibliography [listing] over 1200 books [almost 100 on Ned Kelly]." Sympathy for Kelly is not something read back anachronistically into a distorted past. It began during his lifetime and has continued to the present. I recently came across the following interesting incident in Morna Sturrock’s biography of Bishop James Moorhouse, Bishop of Magnetic Power (2005) while reviewing her book for History Australia, which brings sympathy for Kelly into focus. The second Anglican Bishop of Melbourne, Moorhouse, visited north-west Victoria in October-November 1878. The newspaper headlines spoke of the “Mansfield Outrage,” Sgt. Michael Kennedy having been shot dead by Ned Kelly, alkong with three other cionstables, at Stringybark Creek. His body was brought into Mansfield and Moorehouse was called upon to preach there. Kennedy (and Kelly) were Catholic but Moorehouse visited his grieving widow to console her and also to strongly advise her against viewing “the poor disfigured corpse” of her husband. Half his face had been shot off and a wild animal had chewed off his left ear sometime over the three days his body lay in the bush before it was discovered. "She agreed," wrote Moorhouse, "that I should go and see if the sight were fit for her; and when I told her it would be wicked for her in her state of health to subject herself to such a shock, she went quietly home. I attended the poor Sergeant’s funeral. The Priest asked me to walk with him at the head of the procession."  The funeral service, from St. Francis Xavier’s Catholic Church was quite an ecumenical occasion with Moorehouse leading the procession along with Father Scanlan, Samuel Sandiford, the Anglican rector of Mansfield, and the local Presbyterian minister, the Rev. Reid. In the age of sectarianism this is quite notable. Father Scanlan had ridden by night, “along the wild road from Benalla, with the reins in one hand, and a revolver in the other.” While standing in solidarity with the victims of the crime and insisting that the perpetrators should be tracked down and arrested, at the same time Moorehouse showed remarkable sympathy for the Kelly Gang. "Poor wretches! One cannot help pitying them, crouching among the trees like wild beasts – afraid to sleep, afraid to speak, and only awaiting their execution. But bushranging is so horrible, so ruthless, so utterly abominable a thing, that it must be stamped out at any cost." Two days after the funeral while preaching in the church at Mansfield he repeated these remarks, prayed for the murderers and told the people they should “pity the poor wretches who caused us to mourn over these disasters.”

The funeral service, from St. Francis Xavier’s Catholic Church was quite an ecumenical occasion with Moorehouse leading the procession along with Father Scanlan, Samuel Sandiford, the Anglican rector of Mansfield, and the local Presbyterian minister, the Rev. Reid. In the age of sectarianism this is quite notable. Father Scanlan had ridden by night, “along the wild road from Benalla, with the reins in one hand, and a revolver in the other.” While standing in solidarity with the victims of the crime and insisting that the perpetrators should be tracked down and arrested, at the same time Moorehouse showed remarkable sympathy for the Kelly Gang. "Poor wretches! One cannot help pitying them, crouching among the trees like wild beasts – afraid to sleep, afraid to speak, and only awaiting their execution. But bushranging is so horrible, so ruthless, so utterly abominable a thing, that it must be stamped out at any cost." Two days after the funeral while preaching in the church at Mansfield he repeated these remarks, prayed for the murderers and told the people they should “pity the poor wretches who caused us to mourn over these disasters.”

Not long after the funeral, Moorehouse and his wife stopped at an inn in Benalla for a meal and a change of horses. They were surprised to notice Chief Commissioner Standish, who was overseeing a yearlong search for the Kelly Gang, leave the inn without speaking with them. As the Moorehouses moved on they noticed a mounted policeman up ahead of them and others stationed here and there along their route as if keeping watch over them. Upon returning to Melbourne he was informed that the Kellys were angry at the Bishop’s influencing of public opinion against them and had planned to kidnap him, spirit him away to the mountains and hold him for ransom. While enjoying a smoke in the garden of the inn he had been in range of their rifles. However, some of the Kelly supporters thought such an action would damage their cause and so warned the police; hence the armed escort.

Many alienated small farmers and farm labourers became Kelly “sympathisers.” John McQuilton’s The Kelly Outbreak (1979) describes widespread agricultural ignorance, poverty, and disillusionment in north-east Victoria at this time. Colin Holden’s history of the Diocese of Wangaratta, Church in a Landscape, states that the Kelly Gang enjoyed support in the local community because struggling farm workers saw Kelly’s plight as an exaggerated form of their own situation. Rural newspapers of the day noted that the Kellys also enjoyed support among “the respectable and well-to-do” people, including Anglicans, “who might in other circumstances appear as supporters of law and order.” The Church of England Messenger said that bushrangers could always count on finding “punctual provisions and trusty spies among the settlers in the remote districts.” In discussing the question of whether Kelly should be viewed as a violent psychopathic criminal or a hero of the people, more sinned against than sinner, one of my students asked whether 100 years ago we would be remembering serial killer Ivan Mallatt as favourably as we remember Kelly today. The answer to the question is “no” for many reasons, but one of those reasons is that Kelly was a popular figure in his day. Ivan Mallatt and his kind have no supporters. They are psychopaths who seem to kill for no reason and with no remorse. 38,000 people signed a petition for Kelly’s pardon. No one today advocates for Millatt. Kelly was a violent man enmeshed in the criminal underworld of north-east Victoria in age of widespread police brutality and corruption. Criminals are the results of both nature and nurture; communities produce them as much as women give birth to them. It was “not easy being an Irishman in Queen Victoria’s colony.” People do not commit crimes simply because they are evil and the world is not a place made up of men and women who are either good or evil. We are more complex creatures than that. I think Bishop Moorehouse understood this and so he prayed for the “poor wretches” who made up the Kelly gang and he exhorted his flock to have pity on them. So was Kelly a hero or a criminal? Probably both.

In discussing the question of whether Kelly should be viewed as a violent psychopathic criminal or a hero of the people, more sinned against than sinner, one of my students asked whether 100 years ago we would be remembering serial killer Ivan Mallatt as favourably as we remember Kelly today. The answer to the question is “no” for many reasons, but one of those reasons is that Kelly was a popular figure in his day. Ivan Mallatt and his kind have no supporters. They are psychopaths who seem to kill for no reason and with no remorse. 38,000 people signed a petition for Kelly’s pardon. No one today advocates for Millatt. Kelly was a violent man enmeshed in the criminal underworld of north-east Victoria in age of widespread police brutality and corruption. Criminals are the results of both nature and nurture; communities produce them as much as women give birth to them. It was “not easy being an Irishman in Queen Victoria’s colony.” People do not commit crimes simply because they are evil and the world is not a place made up of men and women who are either good or evil. We are more complex creatures than that. I think Bishop Moorehouse understood this and so he prayed for the “poor wretches” who made up the Kelly gang and he exhorted his flock to have pity on them. So was Kelly a hero or a criminal? Probably both.

If you enjoyed this blog entry you might also enjoy the following: Ned Kelly and the Wesleyan Preacher; The History Wars; "Wiping Out" the Aborigines and The Proposition

4 comments:

Hi Glen

I think you are right about this one. A while back I read 'The True Story of the Kelly Gang' and really couldn't help but feel empathetic to the plight of Ned Kelly. Its really no surprise that many people rallied for him to be pardoned. When you read about how he and his family were treated by authorities and even the feelings within their own family towards each other it does seem to support the notion that people really are a product of their environment.

Hi Donnna. Nice to see you dropping in on my blog. I enjoyed Peter Carey's version of the story too. It did take me a while to get used to the style he used, based as it was on the disjointed parlance of the Jerilderie Letter, but once I got past that the book was quite a revelation.

Could this James Moorhouse be the Wesleyan Minister of the same name who got my Great Great Grandmother Elizabeth Humphreys pregnant in Nelson, New Zealand in 1961?

I always heard the myth of how the holy man that visited Nelson and lanned the building of Nelson Cathedral had got poor young 20 year old Elizabeth up the duff, but thought it was a myth.

Then today, I received a copy of my Grandma's fathers birth certificate, and low and behold - the fathers name is James Moorhouse, and his occupation, Wesleyan Minister.

They never married, she married someone else about 6 years later.

What do you think? Could it be the same man?

Regards,

Lesley F

New Zealand

Hi Lesley,

Thanks for commenting. Sorry it took me a while to reply. I had a technical problem and have not blogged for months. No this would not be your ancestor James Moorhouse as THIS Moorhouse was an Anglican not a Wesleyan Methodist. Must be a different clergyman of the same name.

Post a Comment