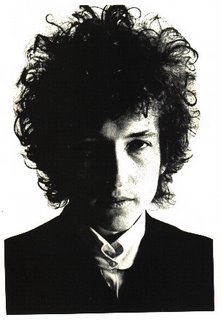

Bob Dylan in Melbourne 1966

I received Martin Scorsese's Bob Dylan film No Direction Home as a birthday gift back in October. It chronicles Dylan's remarkable career up until the world tour in 1966. A few years ago I presented a paper at Deakin University's Go! Melbourne in the 60s Conference entitled "Antipodean Apocalpytic: Bob Dylan in Melbourne 1966." This resulted in an invitation to present the paper again, this time to a pub crowd at the Cornish Arms in Brunswick (at the Dylan tribute night Bob's Birthday Bash) as well as to perform a few songs with my friend Clive Doak (Jokerman, Blind Wille MacTell, She Belongs to Me and another one I can't remember). It was great to read the paper under a single spotlight to such an appreciative crowd. Here are a few excerpts from the paper:

'In 1966, Robert Menzies resigned, Harold Holt instituted conscription for the Vietnam War effort, and assured the American President that Australia would "go all the way with LBJ," Australia switched to decimal currency, the White Australia policy was abandoned, 6 o'clock closing was extended to 10pm, and Bob Dylan toured Donald Horne's "luck country" on an amphetamine-driven wave of success. The press didn't quite know what to make of him (he wasn't a cute mop-top Beatle like the last rock icons to tour). The cultural wasteland of Australia in the 60s was brought face to face with a singer who broke all the rules of vocal delivery, looked like he was from some other planet, and wrote stream-of-consciousness lines such as "jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule," and "praise be to Nero's Neptune; the Titanic sails at dawn." This was apocalytic discourse, revelatory messages mediated from a seemingly otherworldly being to startled recipients. Like all apocalyptic discourse it was "disclosing a transcendent reality...both temporal, insofar as it envisage[d] eschatological salvation, and spatial insofar as it involve[d] another, supernatural world." (J. J. Collins, "Apocalypse: The Morphology of a Genre," Semeia 14 [1979], p. 9.) . Apocalypse had come to the antipodes.'

'In 1966, Dylan was performing "poetry you could dance to," a formula for "reinventing music" that Dylan and Richard Farina had first talked about with Eric von Schmidt on the beach at Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1961 (David Hadju, Positively Fourth Street [London Bloomsbury, 2001], p. 158) . Bob Geldof remembers seeing Dylan perform in Dublin in 1964. "Dylan had scooped the whole of American folk music (folk, blues, country) and married it to the Psalms, the poets, the Old Testament, and hurled it at my head, articulating the inchoate urge I was feeling. Bob moved my head. Mick and Keith [of the Rolling Stones] my hips." (Bob Geldof, "Turn the Bleedin' Noise Down Bobbo!" in Uncut [June 2002], p. 46)

'The English word "apocalpyse" comes from the Greek New Testament word meaning "a revealing" or an "uncovering." It has since developed the additional meaning of the catastrophic end of the world as we know it. Dylan was involved in both. He was blowing the lid off a world that wasn't ready for him, uncovering more than people were often wiling to see. Rock music was meant to be all about sex, violence and teenage angst. Now it had pretensions to art. He had "grown up pop" and "given it brains." (Nik Cohn, Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: Pop from the Beginning [London: Minerva, 1996 reprint of 1969 original], p. 168). The old world of tin-pan alley and "I wanna hold your hand," had to give way to the new world, and none of us would ever be quite the same again. '

'During Bob's mysterious hiatus [after his motorcycle accident at the end of the '66 word tour] the Beatles released Sergeant Pepper, and the whole hippy-trippy, flower power phenomenon reached its height. With baited breath the public waited for what psychedelic offering the "Great White Wonder" would produce as the follow up to the "thin, mercury sound" of Blonde on Blonde. When John Wesley Harding was finally released, in 1967, it was not what anyone had expected. Gone was the frenetic rock of the 1966 tour that a Manchester fan had described as "an apocalyptic roar like a squadron of B52s in a cathedral...wicked, crackling guitar over a vortex of sheer noise." (Mojo [Nov. 1998]: 60), p. 61) Now, sparse acoustic backings underlay an album of mystic Americana, that carried a gentle, reflective country feel, only thi nly masking the continuing apocalyptic. "Even with its overtones of Nashville, hoedown and Grand Ole Opry, it was grim." [Cohn, 169) Though apocalyptic literature is meant to reveal, it also hides, behind cryptic symbols understood only to the initiated. In The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest, the gambler Frankie Lee dies of thirst, in the arms of his friend Judas Priest, after sixteen days and nights foaming at the mouth in a multi-storied whorehouse. An anonymous little neighbour boy, perhaps Dylan himself, looks on and records the whole saga, yet hiding behind the cryptic imagery so that ultimately, as in the final words of the song "nothing is revealed."

nly masking the continuing apocalyptic. "Even with its overtones of Nashville, hoedown and Grand Ole Opry, it was grim." [Cohn, 169) Though apocalyptic literature is meant to reveal, it also hides, behind cryptic symbols understood only to the initiated. In The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest, the gambler Frankie Lee dies of thirst, in the arms of his friend Judas Priest, after sixteen days and nights foaming at the mouth in a multi-storied whorehouse. An anonymous little neighbour boy, perhaps Dylan himself, looks on and records the whole saga, yet hiding behind the cryptic imagery so that ultimately, as in the final words of the song "nothing is revealed."

'Dylan's much publicised conversion to Christianity in 1979 did not see him take an entirely new approach to his art, though it was a personal renewal. The entire body of his work has been preachy, finger-pointing, biblical, and scathingly prophetic, in the best tradition of the Hebrew Bible and of the New Testament. (See Michael J. Gilmour, "They Refused Jesus Too: A Biblical Paradigm in the Writings of Bob Dylan," Journal of Religion and Popular Culture (vol. 1, Spring 2002), www.usack.ca/relst/jrpc/article-dylan.html). The drugs, thankfully, would go, the excesses would reced, the jangling pace and the fury of 1966 would fadse, but the voice of the little Jewish neighbour boy still croaks at us. '

'For a little while, in the Australian Spring of 1966, Dylan gave Melbourne a glimpse of the apocalypse. Amazingly, he has survived. Now an old blues singer, on his latest album, Love and Theft, his ancient voice warns us, that he is still, like a black crow in a pulpit, preaching the Word of God to us and putting out our eyes."

Keep preaching Bob!

3 comments:

That was really good. I enjoyed reading.

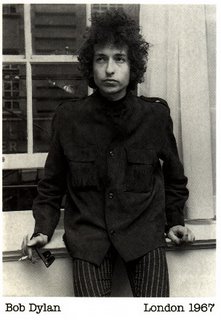

The photo is, of course, London 1966 - not 1967

John Fellows WA

The photo is, of course London 1966 NOT 1967

John Fellows

Post a Comment